Ramblings of a Radiofile

I don’t know what made me take an interest in radios, and all things electrical; I played football in the local park, but they never picked me for the school team. I also played cricket, but as a batsman I was not quick enough to see the ball coming. So, I think I must have had a more sedentary inquisitive nature. My mother used to say that if I was given anything mechanical or electrical I had to take it to pieces to see what it was made of.

I know I was in the junior school at the time. We had just got our first ‘all mains’ Cossor radio, which meant there was no accumulator to be charged each week. These were like glass jars, with a few metal plates inside, and two terminals on the top. It was usually my job to take the thing to a man a few streets away for charging. I always carried it very warily as I knew it was filled with sulphuric acid, which was something to be handled with care. The man had a shed in his back yard for his little business, and on entering you saw a dozen or so accumulators on a bench all ‘sizzling’ away. He would take mine, attach a couple of wires to the terminals, then hand me another in exchange. That was it for another week, provided we used the radio sparingly. Some accumulators had a pointer on the side which moved up or down to show when it needed charging.

Radio, or Wireless as it was known then, was a new medium compared to the variety of communications and entertainment equipment we know today. Not every family possessed one, and if they did, it was used only when necessary for news etc.

Musical entertainment was usually provided by the wind-up gramophone. Sunday afternoon was a favorites, when families would sit in the parlor and listen to their record collection. My father often took the family to the London shows, consequently we had several 12 inch records of the music, which ran at the standard speed, at that time, of 78 revolutions per minute. The needles were supposed to be changed for each record, but you could get some special ’long playing’ needles which would play a dozen or so.

Radio was not something which ‘took off’ quickly, as certain things do today, perhaps because not all homes could afford one. It was only later when war broke out when news and information was vital, that a steady increase in sales began. There were several British Medium Wave stations which could be received, plus a few French, German and Dutch stations. On the Long Wave, you had our own Daventry, and then Radio Luxemburg came along. This station only broadcast in English at certain times of the day with commercial advertisements. It was noted for its programme by the ‘Ovaltinies’, and later, ‘Dick Barton, Special Agent’. In between the adverts, they played ‘pop’ music. Commercial advertising was not allowed in this country at that time, so programmes had to be compiled in this country, and then broadcast by Radio Luxemburg.

In 1964, Radio Caroline, a ‘pirate’ station, began commercial broadcasts from a ship in international waters anchored in the North Sea. With its basis of ‘pop’ music, it attracted more listeners than the BBC. The first competition to the BBC’s 50 years monopoly, began in October 1973 with the London Broadcasting Company, (Capital Radio), a new commercial station broadcasting music and entertainment.

What fascinated me was ‘where did the sound come from?’ With our ‘wind-up’ gramophone you were aware of the needle moving across the record; you could lift it, and put it down again. If you knocked the machine whilst it was playing, the arm would slide across the record with a horrible scratching sound. You were aware then, what was generating the sound. It was tangible, you could understand it. Not so with the radio.

Switching the radio on, you could hear music, or perhaps someone talking. Then, if you pulled the aerial out, it would stop. Put it in and it would start again. A young boy could only conclude that the sound was coming down the aerial. But how? Sometimes we used to play with two tin cans, attached to a long piece of string. If we held the string tight, and shouted into one can, it could usually be heard in the other. But we couldn’t see anyone talking or playing music into the aerial.

Secondly, how was it that for a small movement of the dial, you could pick up music from London and then from Radio Hilversum in Holland? It was something which needed investigating. And that seemed to be the start.

Knowing I was showing an interest in such matters, my uncle Jack gave me a Crystal Set for Christmas. It looked to me like a magical machine with brass terminals, knobs, and the crystal and cat’s-whisker, mounted on an ebony facia. The whole was housed in a highly polished wooden box.

Crystal Sets were the most basic of receivers; a coil of wire, a tuning condenser, (or capacitor in today’s terms), the crystal and cat’s-whisker, and a pair of headphones. The coil and capacitor tuned into the stations, whilst the cat’s-whisker made the signals audible for the headphones.

The crystal, perhaps a piece of gallium, was held in a brass cup, whilst the cat’s-whisker was just a thin piece of wire. The crystal would allow the signal to pass, providing the right spot at which conduction could take place was found by the whisker. Once the whisker touched the sensitive spot, the situation was Go.

A crystal was used as it had the properties of allowing signals ‘one way only’, and more importantly, with the minimum of signal reduction. Thus, with a good aerial and careful tuning, it is surprising how many stations could be received.

One of the faults, of course, apart from the fact that only one person was able to listen at a time, was that any sort of vibration caused the sound to be lost. If someone entered the room and closed the door somewhat noisily, the whisker would become dislodged and the sound would disappear. The little lever which moved the whisker would then have to be ‘jiggled’ around a bit until another conducting spot was found. Fascinating stuff for a young boy.

As time went by, I managed to gather together a few bits and pieces of radio components which people had thrown out for the dustman. The father of my pal Maurice Scott worked for the Corporation, and if he found any discarded old radio parts, he would leave them at my door. It was not much, mostly junk, but ‘pennies from heaven’ to me. Even an old metal chassis was at least a start.

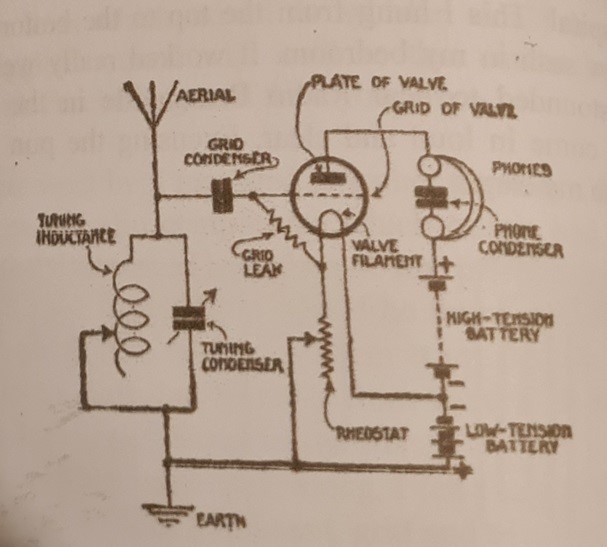

When my first valve came along, I felt I was on my way. It was a simple triode – filament, grid and plate (now called the anode).

However, unlike the crystal set which required no power, it needed an accumulator for the two volt filament, a ‘grid bias’ battery, and 120 volts for the high tension supply. High tension batteries were expensive, and beyond my means, so an ‘eliminator’ which gave a similar voltage from the mains supply was the answer. The grid bias was a flat battery, a few inches long and narrow with connections to tap-off between 1.5 and 9 volts negative.

As a prospective ‘ham’ I was interested in the Short Waves, and so I built my ‘one valver’ accordingly, winding the coils around a cardboard tube. Someone gave me an eliminator; it was a massive thing, nearly a foot square in a steel cabinet, and seemed to weigh a hundredweight. Nevertheless it worked, and more than that, it had a switch which charged the accumulator when it was not in use.

My one valve masterpiece and its associated power supplies, just fitted into a large orange box which I used as a bedside cabinet. For an aerial I acquired a length of copper wire which I wrapped around a broom handle into a long spiral. This I hung from the top to the bottom of the window sash in my bedroom. It worked really well, and I was astounded to hear Radio Brazzaville in the Belgian Congo come in loud and clear. Excusing the pun – it was music to my ears.